How do we represent text as inputs to ML models? Models work with numbers, not words, so we need to convert text into numerical vectors that capture as much meaning as possible.

Numerical word representations

- one hot encoding:

- for a vocabulary size of 10, the one-hot vector of the 4th word in the vocabulary would be: → it’s too high-dimensional, and no similarity

- bag of words:

- count frequency of each word in a sentence (huge loss, loses order)

- dense vector of embeddings

- learned numerical vectors using semantics

- each words gets a dense 100-300 dims vector

- similar words get similar vectors

- learned automatically through training

- embedding matrix = giant lookup table

- PyTorch

nn.Embeddingretrieves rows from that matrix

Language Modelling

Language modelling is concerned with capturing statistical properties of text: predicting the next word or missing word within a certain context.

Models like Word2Vec learn embeddings by optimizing such prediction tasks. Its architecture key ideas:

- CBOW: predict center word from context words

- Skip-gram: predict context words from center word

- Shallow networks but learn excellent embeddings

RNNs

A recurrent neural network maintains a hidden state across time: Which means:

- at time , RNN reads input

- updates hidden memory

- shares the same parameters at every time-step

- can process variable-length sequences

A key property is inductive bias for sequences: RRNs assume the next output depends on previous ones inductive bias (also known as learning bias) of a learning algorithm is the set of assumptions that the learner uses to predict outputs of given inputs that it has not encountered. Inductive bias is anything which makes the algorithm learn one pattern instead of another pattern

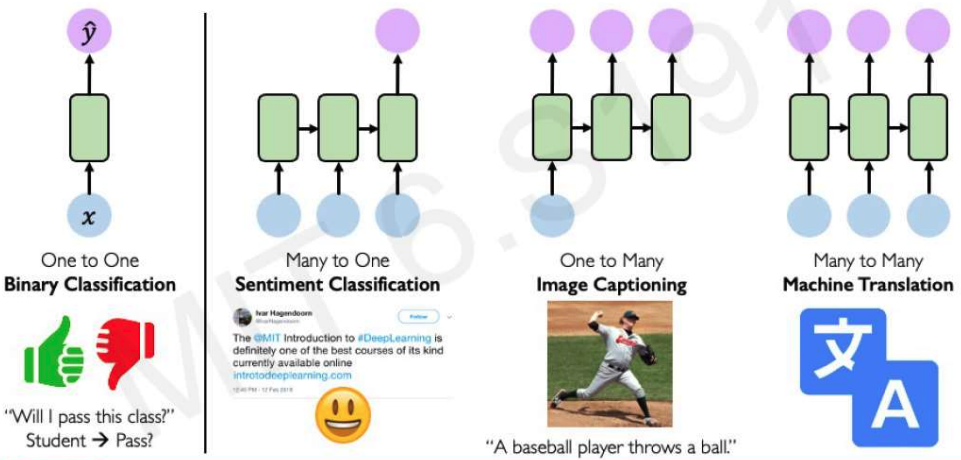

Types of sequence prediction

- One to One: binary classification

- Many to One: sentiment classification

- One to Many: image captioning

- Many to Many: machine translation

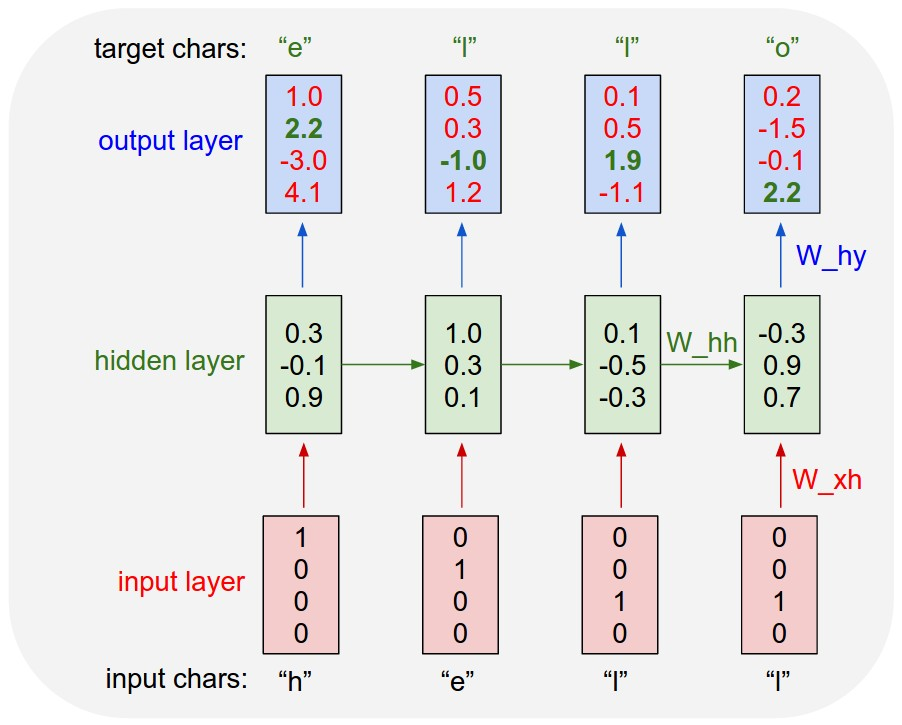

example of next char prediction (from daddy karpathy)

RNN implementation

RNN implementation

rnn = RNN()

y = rnn.step(x) # x is an input vector, y is the RNN's output vector

class RNN:

# ...

def step(self, x):

# update the hidden state

self.h = np.tanh(np.dot(self.W_hh, self.h) + np.dot(self.W_xh, x))

# compute the output vector

y = np.dot(self.W_hy, self.h)

return yexposure bias

when we “teacher forcing” during training (feeding the true previous word as input) then during test the model will feed its own prediction back and that mismatch is exposure bias. the issue is that the model has no idea how to correct an error. this is because the model never trained on its own (possibly wrong) predictions.

backpropagation through time (BPTT)

unrolling an RNN across T steps, and back-propagating through all of it is computationally expensive for long sequences, and gradients will vanish/explode. therefore, we use truncated BPTT and only backprop through last k timesteps.

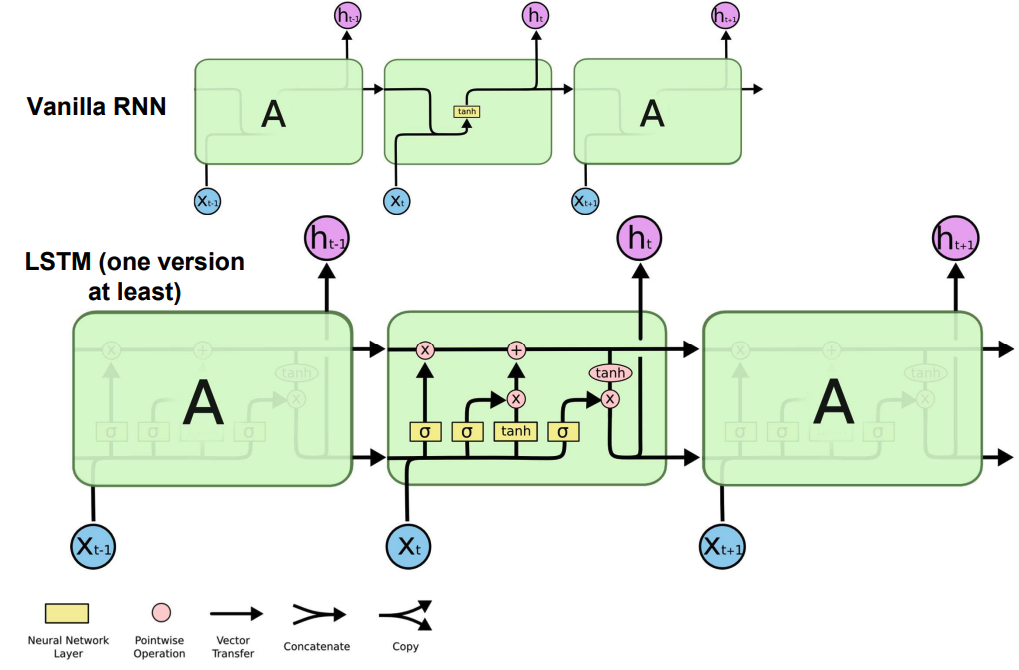

LSTM/GRU

[paper]((https://www.bioinf.jku.at/publications/older/2604.pdf) / post How do we track long-term dependencies without vanishing gradients? LSTM solves this by using a cell state and gating mechanisms.

Instead of overwriting state at every step:

- keep a “long term memory” (cell state )

- gates control what to forget/add/keep (forget gate, input gate, output gate respectively)

GRU is a simpler variant with no explicit cell state, it only uses the hidden state.

remaining issues

Even LSTMs and GRUs struggle with extremely long dependencies (paragraph-level) and parallelization (it must process sequentially) unaware what information might serve later steps best

Unlike feedforward, RNNs are Turing complete tho! We can simulate loops, implement memory, and extended to differentiable computers.